Continued from Part 1 here: https://outsideinlens.substack.com/p/attention-factory-the-story-of-tiktok

B) The Proof of Concept (POC): Evolution of Musical.ly

“I was on (the) Caltrain one day, from San Francisco to Mountain View, and it was crowded by teens. Observing their behavior, 50 percent were listening to music, and the other 50 percent were taking photos and videos with their speaker on top to add music. Teens are so passionate about social media, photos, videos, and music, that it made me think. Can we combine these three very powerful elements into one app and build a social network for music videos?” – Alex Zhu Insight, leading to development of Musical.ly

To understand the sentiment of the users, Alex spent a great deal of time on the app and registered multiple fake accounts pretending to be a regular user. He would comment on others’ videos and ask why they shared or created certain content, a user research tactic commonly deployed by Chinese tech bosses. They brought hundreds of their early loyal users over into WeChat messaging groups to have daily conversations. For every new feature, they shared mockups to gain immediate direct feedback. One of the first changes made based on these talks was to extend the length limit of the videos to 15 seconds to match the limit imposed by Instagram, the platform where teens wished to share their videos most.

In trying to encourage a sense of community amongst their early adopters, the team discovered that the most effective way was to regularly promote “challenges.” Challenges are essentially user-generated video memes. A challenge sets up a replicable, cookie-cutter structure that allows anyone to take part and make their own version. They could be anything from a simple set of dance moves to a goofy prank. Viral video memes were already blooming on other social media platforms before Musical.ly. Prominent examples included the “Harlem Shake,” which saw groups of people dancing together crazily, and the “ice bucket challenge” where celebrities would challenge each other to pour ice-cold water on themselves to promote ALS awareness.

The term “challenge” explicitly communicates the participatory and fun nature of the format. On Musical.ly, users were encouraged to join trending challenges and make their own version. Challenges were a way of educating users and showcasing new ways to create videos. It also allowed the Musical.ly team to have greater control over the direction of content creation. The challenges gave users a purpose to participate and create videos rather than just passively watch others. “The key difference between Musical.ly and Vine is that on Musical.ly we lowered the barrier to content creation, so all the consumers are creators at the same time,” explains Alex. As he saw it, lowering the barrier to content creation was critical to Musical.ly’s success, where all content was produced by users.

The most significant barrier to people creating videos wasn’t a technical one. All new breed of short video mobile apps had easy-to-use mini-editing studios built in. Young users especially had no trouble working out how to add music, text and use the recording function. Shyness also wasn’t a problem as many young users loved recording themselves. A more substantial barrier was one of creativity & inspiration—coming up with a concept. Most users need to be inspired.

But the Musial.ly team found that the promotion of daily challenges was a much more effective way to build a regular habit of content creation. Users didn’t need to think that much. All they had to do was to follow the crowd and add their spin on an already familiar theme. Copying others wasn’t just okay; it was actively encouraged. Challenges also helped combat the final most difficult barrier of all—motivation. There was a sense of immediacy. Users either chose to participate in the fun challenge while it was trending today or risk missing out. Participation also gave people a sense of being part of a wider community.

“Sometimes slow growth is worse than failing fast,” – Alex Zhu Reflection

Being a platform where all the content is user generated required them to think carefully about nurturing an active community. They needed to ensure there was a stable group of committed creators regularly producing high-quality content. This would provide them with stickiness and longevity, hopefully avoiding the fate of being yet another flash in the pan small social media platform. Alex compared the strategy they took to that of “nation-building.”

“When you want to grow early on, you want to be a brush, meaning you have to be very specific; you have to solve a specific need very well… Later you want to be a canvas; you want all kinds of things to happen on this blank canvas.” This was the metaphor Alex used to explain how he envisioned Musical.ly’s progression.

Being a utility tool allowed Musical.ly to get its foot in the proverbial door and gave it the chance to leverage this initial traction to build something bigger. Once the tool helped attain a critical mass of content and creators, it could become a content platform, satisfying people’s desire for passive entertainment consumption—TV for mobile. Once a critical mass of users was attained, it could foster connections between those users, evolving into a social platform, satisfying people’s desire to connect and seek status. These values reinforce each other, as content becomes the starting point for interaction and status creation. Conversely, the social connections built through that app would keep users coming back to consume more content. Above: An outline of the progression from tool to social and content platform.

“In doing user interviews and digging deeper into our data, we discovered Musical.ly was not a social network, it was a content platform,” revealed James Veraldi, an American working in Shanghai on product strategy with the Musical.ly team. Musical.ly had spent years thinking it was the next Instagram; when in fact, it was the next YouTube.

In a short 2017 presentation at a Tencent Media event in Shanghai, Louis outlaid his thoughts regarding the use of technology to improve the platform’s content distribution mechanism. He presented three models for the distribution of content. A traditional model that relied exclusively on a subscription mechanism which was viable because it only needed to ensure the top 1% of premium content reached people. Secondly, a social network model where the problem became how to distribute the top 30% most engaging content well. This was equivalent to the model used by Twitter. The final model was a vision for the future of Musical.ly, one powered by personalized recommendation, where it was possible to match all of the platform’s long tail niche content to an appropriate audience.

The three-pronged strategy of ByteDance consisted of “Xigua (Watermelon) Video,” which imitated YouTube, the clear global leader in online videos, and “Huoshan (Volcano) Short Video,” which imitated Kuaishou, the clear leader in China’s short video market at the time. Finally, the wildcard in the mix was A.me, later known as Douyin, a clone of Musical.ly, the Western market leader of short videos for young people. Instead of gathering established influencers, the team banded together a group of around twenty official “A.me endorsed creators” who were enlisted from other platforms, including Musical.ly, to create videos. The goal was to have their content inspire and educate other early users to create videos.

Treat Them Like Royalty: The first thing the team did was to treat its existing small band of popular creators like royalty. The operations team would chat with them individually every day, earnestly listening to their ideas, and making them feel they were participating in the platform’s growth and molding its direction. If a Beijing-based user encountered a problem that was not easy to explain online, they would be invited to chat over a free meal at ByteDance’s company cafeteria. Just like Musical.ly, the team made use of theme-based challenges to build communities and actively encouraged users to riff off each other’s creations, building upon shared memes. Users were free to initiate their own challenges, which helped the team learn what kind of content people preferred and guide them in selecting their official challenges. Many of the first official challenges originated not from the team but ideas that came out when talking with the early video creators. They would reward the best video creators with gifts such as cameras, celebrity merchandise, or snacks, yet another way to make people feel special. Top content creators were ranked within the app on “Most Popular List,”“Most Active List,” or “Weekly Rookie List”– helping foster a sense of community.

The tactics A.me was using are part of what is termed “operations.” Heavy reliance on operations to achieve growth is one of the defining characteristics of the Chinese internet. At Western tech companies, the role of user acquisition typically falls under the marketing, sales, or growth teams, which tend to systematically achieve user growth through highly scalable data and technology-driven methodology. In addition to these established techniques, Chinese companies also favor using manual, labor-intensive methods to promote and grow their platforms. Examples include paying for celebrity endorsements and media exposure, operating promotional accounts on other platforms, or running regular competitions and festival holiday promotions. Operations teams are typically active all day, maintaining relationships with outside stakeholders, including users, creators, and promotional partners.

A.me went as far as assigning account managers to individual creators who would do everything possible to please them, even buying them dinners and helping with school assignments or relationship issues. Next to the team’s workstation was a big box filled with all kinds of props for shooting videos, from wigs and glasses to funny placards. When an early user celebrated their birthday, the operations team would record an exclusive video for them. Around Christmas time, a team intern even went out his way applying for a credit card to order a Christmas tree on Amazon for Xue Lao’shi, an influential Canadian student who had initially refused to join.

“To abandon a project, mainly we look at the data,” described ByteDance executive Chen Lin, “but the leader also has to use their judgment.”A leader needs to judge why the data is bad. Is the market segment smaller than they thought? Have they misjudged people’s needs? Or did they just execute poorly? Perhaps ByteDance doesn’t have the right company DNA to do something targeted at such young people?

Address the problem of cultivating quality young Content Producers: The solution was art college students. The Douyin team went deep into art schools across the country to scout for good-looking students to be its users. Altogether, the team convinced hundreds of them to join, with the promise to help them get famous online. This proved highly effective. The influx of users helped build an original content pool and establish the app’s tone as cool and fashionable. The operations team then started to manipulate the visibility of videos to encourage the type of trendy content they wished to cultivate. Consequently, videos that didn’t conform to the community’s tone and values would struggle to gain visibility. Douyin mobilized its entire staff to lure in creators from competitors. They scouted for suitable talent across all major Chinese social media platforms and even overseas Chinese on Musical.ly, messaging them one by one. To speed up the process, they also began to strike deals with “multi-channel networks” (MCNs), a type of organization that emerged in YouTube’s early years to represent and professionally manage a collective of creators.

In a presentation discussing the rise of Douyin, Kelly Zhang drew attention to four factors—full-screen high definition, music, special effects filters, and personalized recommendations. ByteDance’s “powerful weapon,” to quote the head of its AI Lab, was its content recommendation engine and a pre-existing database of millions of user-profiles and interest graphs. “Every one of us has an interest graph in the backend that ordinary users can’t see. For example, the celebrities I am interested in, the ten companies I care about the most, explained Yiming in one interview

ByteDance put in place a deliberate and systematic strategy to broaden the platform’s content extending into all kinds of mid-tail and long-tail content niches. Travel, food, fashion, sports, games, pets; every major category had a rich and diverse body of content to satisfy all tastes. Promotions shifted from signing big trendy celebrities that appealed mostly to young people into rapidly accelerating content diversity and building a platform more accessible to the mass.

C) The Beginnings of TikTok:

Going Global with a New Identity - TikTok:In the internet world, the fixed costs of product development were high, but the marginal cost of serving an incremental new user was often close to zero

One lesson learned from Douyin had been that user-generated content apps first need to cultivate a committed group of local, high-quality seed creators that define the tone of the community and can generate memes for others to mimic. That took time. Rushing in and spending heavily on ads without any kind of community would be counterproductive.

To address a widespread cultural aversion to individualism, the operations team emphasized challenges that allowed people to participate together in groups and filters that could be used to make faces less recognizable, reducing self-consciousness and allaying concerns over physical appearance.

Globalize Products, Localize Content: Localized and standardized fuse together creating a tailored experience for each market.

Standardized Elements – universal across all markets: Branding (the TikTok name, logo and distinctive visual identity), UX/UI (the core features and design, product logic), Technology (recommendation, search, classification, facial recognition)

Localized Elements – Content (pool of recommended videos), Operations (marketing, promotion and growth)

Ancillary Services could be localized once the user base reached scale. These included: Commercialization (ad sales, business development), Others (government relations, legal and content moderation)

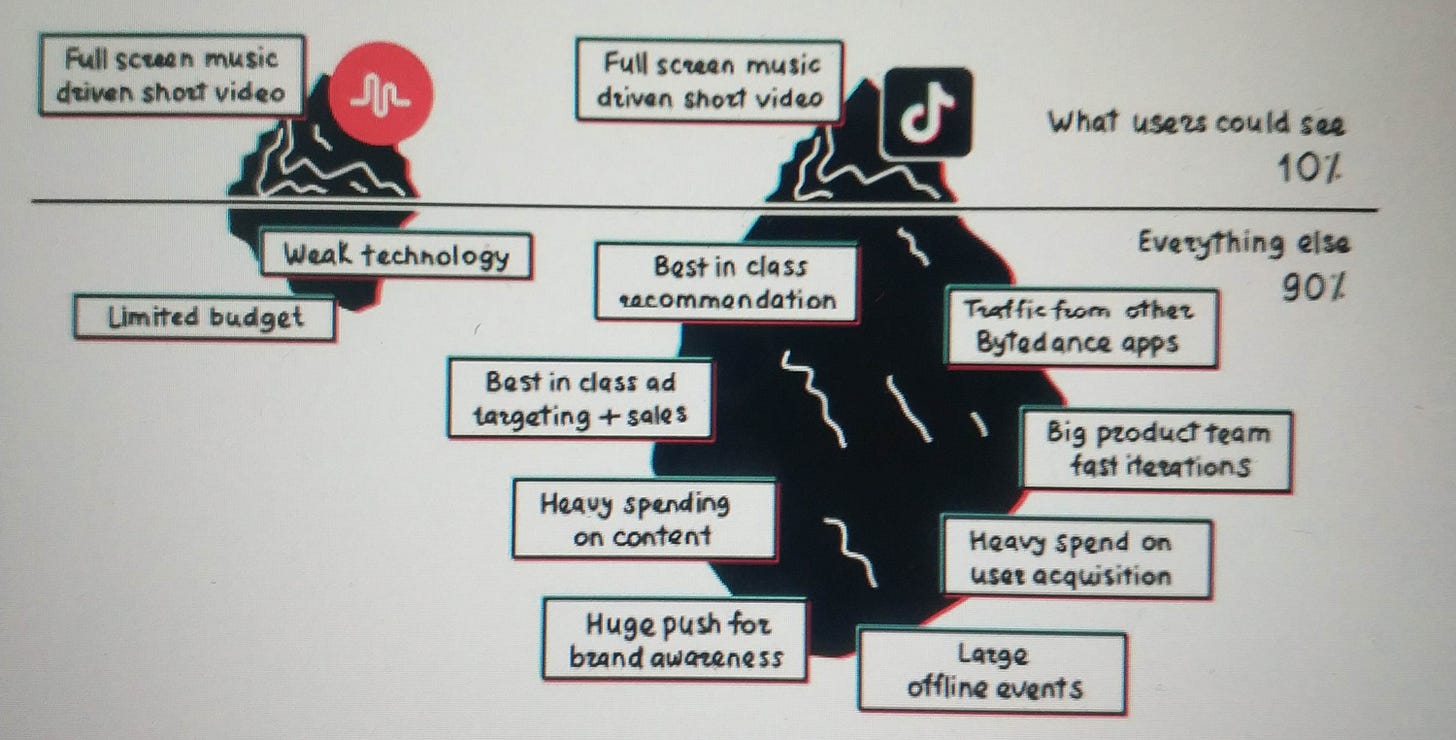

Musical.ly broke all the standard promotional rules. They didn’t create adverts. They didn’t subsidize content creators, and they didn’t pay celebrities. Since its founding, Musical.ly had spent almost nothing on marketing. Instead, they relied on word of mouth and leaned heavily into fostering strong user communities. Groups of highly motivated super fans ran the company’s various social media accounts on other platforms and organized offline meet-ups, all without pay. Some users loved Musical.ly so much they just wanted to help. Musical.ly and Douyin/TikTok seemed similar at first glance, but this was only the tip of the iceberg.

80% of Douyin’s revenue was attributed to advertising, including multiple formats, such as sponsored brand challenges and full-screen adverts that played immediately upon opening the app. Among the various formats, the lion’s share of revenue came from the “in-feed video ads.” These adverts took over the entire screen and played automatically, appearing like a regular TikTok video with just a tiny advert label located at the bottom of the screen next to the video’s description text. Examples of Douyin’s various monetization models, included in-feed video ads, games, virtual gifting, and e-commerce. Marketers quickly worked out that if they made their promotion look like a typical user generated video rather than a professional, slick, polished advert, they could easily trick ad-adverse users into watching the first few seconds, enough time to get their message across.

Another monetization method is platform commissions from “Star-Chart,” ByteDance’s official influencer data management platform. Brands that wish to work with influencers on Douyin must run their campaigns through Star-Chart or risk having the promotional video removed without notice. The platform takes a cut of all fees paid by brands to influencers. There are also revenues from live-stream show tipping and live e-commerce. “Extended businesses” included revenues generated through games, paid knowledge, and e-commerce. “Others” included revenues generated through blue tick account verification fees and “DOU+,” a system through which any user or creator can pay the platform to boost a video’s visibility.

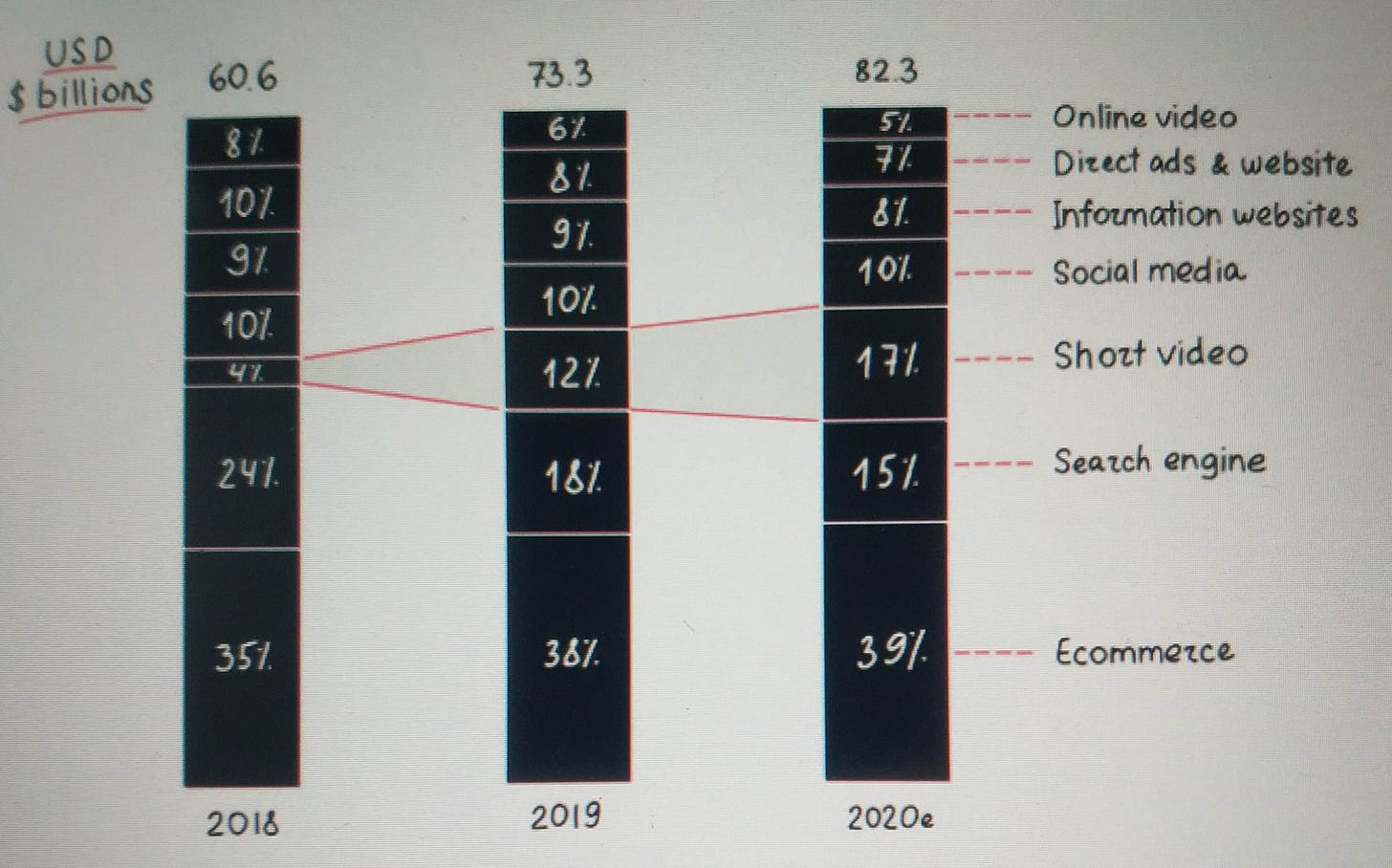

Short video became China’s second-largest advertising category behind e-commerce and exceeding search, a shift that was primarily led by Douyin.

The signup process was significantly streamlined, removing the need to register or log in with an existing account. New users only needed to select from a list of interests (e.g., animals, comedy, and art) and start watching videos within seconds. The app would use a “shadow profile” based on the device ID, which allowed for personalization of content even for those without registered accounts. Asking someone to create an account before they even knew if they liked the app was putting the horse before the cart. The new process allowed people the freedom to experience TikTok without committing

The switch from “Featured” into “For you” was a move from a feed that relied on a hybrid mix of curation and recommendation into one driven entirely by recommendation. The goal was simple — to find the clips that got the most people to click on a big blue “install” button. TikTok was acquiring new users at a much faster rate than Musical.ly. It was then accurately and efficiently matching those users with niche content based on their personal preferences in a way that Musical.ly never could. The algorithmic nature of the platform’s content distribution makes it easy to “tilt the table” in favor of specific content types. ByteDance could reduce exposure to monotonous videos of teenagers lip-syncing and dancing and instead highlight the growing variety of new content categories such as magic tricks, street comedy, sports, or arts and crafts.

Due to the massive influx of users driven by the big-spending on ads, creators found it easy to grow large fan bases quickly due to the imbalance between the supply of and demand for good content. Instagram, YouTube, and others were saturated with people competing for attention. TikTok was wide open and began to attract its own batch of content creators and online marketers—eventually, those looking to gain attention online will always follow the numbers. The dynamic was similar to the metaphor Alex Zhu had used years earlier with Musical.ly – to encourage immigration to your new country, “some people need to get rich first.”

The Power of Memes: Examples of the various video meme formats included – Reveal (Don’t judge me challenge), Dance (The Shiggy Dance Challenge), Challenge (Bottle Cap Challenge), Filter (Mirror Reflection Challenge), Concept (Gummy Bear Challenge)

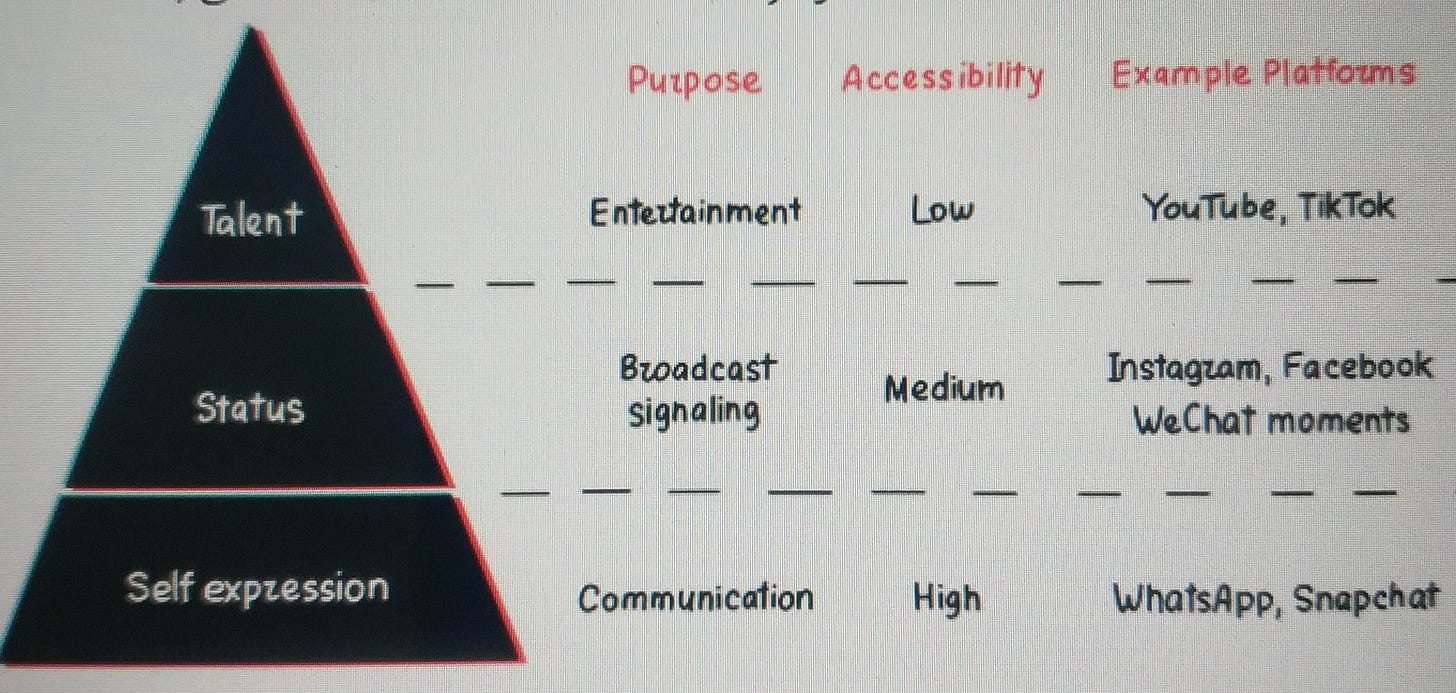

TikTok is primarily an Entertainment Platform. The ‘social’ aspect is relatively weak to the point of being almost non-existent for most users beyond reading, writing, and liking strangers’ comments, similar to how most use YouTube. (Snapchat’s) Spiegel has proposed that entertainment content had the potential to draw people away from more influencer-based status content, given that it is more enjoyable and fun.

(Snapchat’s) Spiegel’s pyramid has helped illustrate how they reasoned TikTok was not a threat to them. The core value of the two platforms was very different. TikTok provides people with entertainment from strangers, while Snapchat connects friends. TikTok could be viewed as the true smartphone era successor to television. The simple swipe-up motion to load the next video was psychologically similar to flicking between TV channels with a remote control. Not knowing exactly what is coming next provides an addictive element of anticipation.

TikTok worked without any need to register an account, subscribe to channels, add friends or expend mental effort choosing which piece of content to consume. Just like television, one simply turns it on. Accessible and intuitive, TikTok was a place for people to zone out and relax. Building a basic TikTok clone and gaining a small market share was easy. Creating a superior version of TikTok, once it had become established in a market, was exceedingly difficult.

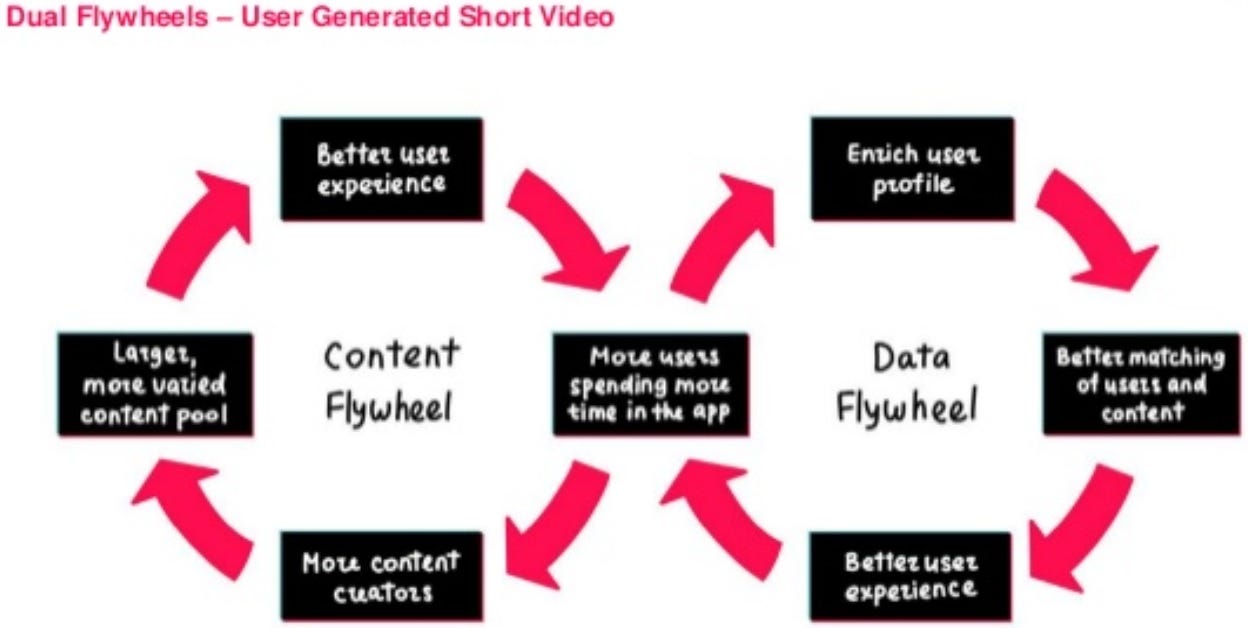

TikTok’s advantage is in its automated video classification and content recommendation systems. The technology allowed for superior matching of long-tail content with users, which further amplified the already existing advantage in content. The more time users spent in TikTok, the more detailed their user profile interest graph became. Put simply—the more you used TikTok, the more personalized it became. This dynamic ensured the early experience of using any clone would always be inferior. Other technical barriers that competitors would struggle to match included the app’s sophisticated use of computer vision to automate the classification and tagging of videos. It was also continually releasing novel and creative augmented reality video filters.

Arguably the most potent defense was the rich ecosystem of skilled video creators. These people invested time and creativity into making unique content for the platform that was timely and meaningful to their niche audiences. TikTok had the most diverse and vibrant ecosystem of short video content creators. Building that community took time and could not be easily recreated at scale. Potential new competitors to TikTok would risk running into the same issues as Tencent’s Weishi—people would try out the alternative app. Yet, once they discovered it had inferior content, they would simply give up and move back to TikTok. Check out the TikTok’s dual virtuous flywheels

Fostering a healthy ecosystem of creators required three things. Firstly, users need to convert into becoming creators. Secondly, creators need to be able to find their audience and build a following. Lastly, they need a way to monetize that following either directly or indirectly. TikTok had considered all three steps.