Thinking in Bets - My Notes

GTM (Go-to-Market) Series

In this edition of the Outside In GTM (Go-to-Market) Series, we try and cover a novel topic of sorts – Thinking in Bets. All Thanks to the classic book written by Annie Duke, we will cover aspects of better decision making that occupies most of our days – figuring out budget allocations, spending energies on a promising lead vs. a symbolic one, combinations for a pricing proposal, meeting or avoiding competition moves, team appraisals and so on. Rather than visualizing plans and outcomes in black and white – success or failure – we must re-calibrate our analysis basis ‘probabilities of outcomes’…

I found the book to be a splendid read that can not only help personally but even professionally, as we think through our decision-making process on a daily basis. I strongly recommend everyone to read the book and this post (!), with an “Outside In lens” of a “GTM Strategy” playbook – applicable to most scenarios in our regular corporate life…

I hope you will feel the same ‘enlightening’ feeling after reading this post…

Thinking in Bets, with Annie Duke

1) Thinking in bets starts with recognizing that there are exactly two things that determine how our lives turn out; the quality of decisions and luck. Learning to recognize the difference between the two is what thinking in bets is all about.

2) To start, our brains evolved to create certainty and order. We are uncomfortable with the idea that luck plays a significant role in our lives. We recognize the existence of luck, but we resist the idea that, despite our best efforts, things might not work out the way we want. It feels better for us to imagine the world as an orderly place, where randomness does not wreck havoc and things are perfectly predictable. We evolved to see the world that way. Creating order out of chaos has been necessary for our survival. When our ancestors heard rustling on the savannah and a lion jumped out, making a connection between “rustling” and “lions” could save their lives on later occasions. Finding predictable connections is, literally, how our species survived.

3) Michael Shermer, in The Believing Brain, explains why we have historically (and prehistorically) looked for connections even if they were doubtful or false. Incorrectly interpreting rusting from the wind as an oncoming lion is called a type 1 error, a false positive. The consequences of such an error were much less grave than those of a type 2 error, a false negative. A false negative could have been fatal: hearing rustling and always assuming it’s the wind would have gotten our ancestors eaten, and we wouldn’t be here. Seeking certainty helped keep us alive all this time, but it can wreak havoc on our decisions in an uncertain world.

4) Admitting that we don’t know has an undeservedly bad reputation. Of course, we want to encourage acquiring knowledge, but the first step is understanding what we don’t know. In science, “I don’t know” is not a failure but a necessary step toward enlightenment.

5) What makes a decision great is not that it has a great outcome. A great decision is the result of a good process, and that process must include an attempt to accurately represent our own state of knowledge. That state of knowledge, in turn, is some variation of “I’m not sure”.

6) What good poker players and good decision-makers have in common is their comfort with the world being an uncertain and unpredictable place. They understand that they can almost never know exactly how something will turn out. They embrace that uncertainty and, instead of focusing on being sure, they try to figure out how unsure they are, making their best guess at the chances that different outcomes will occur. The accuracy of those guesses will depend on how much information they have and how experienced they are at making such guesses. This is part of the basis of all bets.

7) When we think in advance about the chances of alternative outcomes and make a decision based on those chances, it doesn’t automatically make us wrong when things don’t work out. It just means that one event in a set of possible futures occurred. Look how quickly you can begin to redefine what it means to be wrong.

8) Decisions are bets on the future, and they aren’t “right” or “wrong” based on whether they turn out well on any particular iteration. An unwanted result doesn’t make our decision wrong if we thought about the alternatives and probabilities in advance and allocated our resources accordingly. When we think probabilistically, we are less likely to use adverse results alone as proof that we made a decision error, because we recognize the possibility that the decision might have been good but luck and/or incomplete information (and a sample size of one) intervened.

9) Maybe we made the best decision from a set of unappealing choices, none of which were likely to turn out well. Maybe we committed our resources on a long shot because the payout more than compensated for the risk, but the long shot didn’t come in this time. Maybe we made the best choice based on the available information, but decisive information was hidden and we could not have known about it. Maybe we chose a path with a very high likelihood of success and got unlucky. Maybe there were other choices that might have been better and the one we made wasn’t wrong or right but somewhere in between. The second-best choice isn’t wrong. By definition, it is more right (or less wrong) than the third-best or fourth-best choice.

10) When we move away from a world where there are only two opposing and discrete boxes that decisions can be put in – right or wrong – we start living in the continuum between the extremes. Making better decisions stops being about wrong or right but about calibrating among all the shades of grey.

11) In most of our decisions, we are not betting against another person. Rather, we are betting against all the future versions of ourselves that we are not choosing. Whenever we make a choice, we are betting on a potential future. We are betting that the future version of us that results from the decisions we make will be better off. At stake in a decision is that the return to us (measured in money, time, happiness, health, or whatever we value in that circumstance) will be greater than what we are giving up by betting against the other alternative future versions of us.

12) The futures we imagine are merely possible. They haven’t happened yet. We can only make our best guess, given what we know and don’t know, at what the future will look like. When we decide, we are betting whatever we value (happiness, success, satisfaction, money, time, reputation, etc.) on one of a set of possible and uncertain futures. That is where the risk is.

13) Instead of altering our beliefs to fit new information, we do the opposite; altering our interpretation of that information to fit our beliefs. Whether it is a football game, a protest, or just about anything else, our pre-existing beliefs influence the way we experience the world. That those beliefs aren’t formed in a particularly orderly way leads to all sorts of mischief in our decision-making.

14) The more objective we are, the more accurate our beliefs become. And the person who wins bets over the long run is the one with the more accurate beliefs.

15) The more we recognize that we are betting on our beliefs (with our happiness, attention, health, money, time, or some other limited resource), the more we are likely to temper our statements, getting closer to the truth as we acknowledge the risk inherent in what we believe.

16) We would be better served as communicators and decision-makers if we thought less about whether we are confident in our beliefs and more about how confident we are. Instead of thinking of confidence as all-or-nothing (I’m confident or I’m not confident), our expression of our confidence would then capture all the shades of grey in between.

17) When we work toward belief calibration, we become less judgmental of ourselves. Incorporating percentages or ranges of alternatives into the expression of our beliefs means that our personal narrative no longer hinges on whether we were wrong or right but on how well we incorporate new information to adjust the estimate of how accurate our beliefs are. There is no sin in finding out there is evidence that contradicts what we believe. The only sin is in not using that evidence as objectively as possible to refine that belief going forward.

18) Acknowledging that decisions are bets based on our beliefs, getting comfortable with uncertainty, and redefining right and wrong are integral to a good overall approach to decision-making.

19) Be a data sharer. That’s what experts do. In fact, that’s one of the reasons experts become experts. They understand that sharing data is the best way to move toward accuracy because it extracts insight from your listeners of the highest fidelity. What the experts recognize is that the more detail you provide, the better the assessment of decision quality you get.

20) Communicating with the world beyond our Group: First, express uncertainty. Second, lead with assent. Third, ask for a temporary agreement to engage in truth-seeking. Finally, focus on the future.

21) We are generally more rational about the future than the past. It’s harder to get defensive about something that hasn’t happened yet.

22) When we validate the other person’s experience of the past and refocus on exploration of the future, they can get to their past decisions on their own.

23) When we make in-the-moment decisions (and don’t ponder the past or future), we are more likely to be irrational and impulsive. This tendency we all have to favour our present-self at the expense of our future-self is called temporal-discounting.

24) When we think about the past and the future, we engage deliberative mind, improving our ability to make a more rational decision. When we imagine the future, we don’t just make it up out of whole cloth, inventing a future based on nothing that we have ever seen or experienced. Our vision of the future is rooted in our memories of the past. The future we imagine is a novel reassembling of our past experiences. It shouldn’t be surprising that the same neural network is engaged when we imagine the future as when we remember the past. Thinking about the future is remembering the future, putting memories in a creative way to imagine a possible way things might turn out.

25) The way we field outcomes is path dependent. It doesn’t so much matter where we end up as how we got there. What has happened in the recent past drives our emotional response much more than how we are doing overall. That’s how we can win $100 and be sad, and lose $100 and be happy. The zoom lens doesn’t just magnify, it distorts.

26) Our feelings are not a reaction to the average of how things are going. Our in-the-moment emotions affect the quality of the decisions we make in those moments, and we are very willing to make decisions when we are not emotionally fit to do so.

27) We shouldn’t plan for our future without doing advance work on the range of futures that could result from any given decision and the probabilities of those futures occurring.

28) Betting on a Future: Belief → Bet → (Set of Outcomes: Future A, B, C, D, Etc.). Any decision can result in a set of possible outcomes. Figure out the possibilities, and then take a stab at the probabilities. We imagine a range of potential futures. This is also known as scenario planning.

29) Just as great poker players and chess players (and experts in any field) excel by planning further into the future than others; our decision-making improves when we can more vividly imagine the future, free of the distortions of the present. By working backward from the goal, we plan our decision tree in more depth, because we start at the end. When we identify the goal and work backward from there to “remember” how we got there, the research shows that we do better. According to a HBR study, “Prospective hindsight” – imagining that an event has already occurred – increases the ability to correctly identify reasons for future outcomes by 30%

30) The most common form of working backward from our goal to map out the future is known as backcasting. In backcasting, we imagine we’ve already achieved a positive outcome, holding up a newspaper with the headline “We Achieved Out Goal!” Then we think about how we got there.

31) We all like to bask in an optimistic view of the future. We generally are biased to overestimate the probability of good things happening. Looking at the world through rose-colored glasses is natural and feels good, but a little naysaying goes a long way. A premortem is where we check our positive attitude at the door and imagine not achieving our goals.

32) Backcasting and premortems complement each other. Backcasting imagines a positive future; a premortem imagines a negative future. Despite the popular wisdom that we achieve success through positive visualization, it turns out that incorporating negative visualization makes us more likely to achieve our goals. Research has consistently found that people who imagine obstacles in the way of reaching their goals are more likely to achieve success, via a process called as “mental contrasting”.

33) We make better decisions, and we feel better about those decisions, once we get our past-, present- and future-selves to hang out together. This not only allows us to adjust how optimistic we are, it allows us to adjust our goals accordingly and to actively put plans in place to reduce the likelihood of bad outcomes and increase the likelihood of good ones. We are less likely to be surprised by a bad outcome and can better prepare contingency plans.

34) One of the goals of mental time travel is keeping events in perspective. To understand an overriding risk to that perspective, think about time as a tree. The tree has a trunk, branches at the top, and the place where the trunk meets the branches. The trunk is the past. A tree has only one, growing trunk, just as we have only one, accumulating past. The branches are potential futures. Thicker branches are equivalent of more probable futures, thinner branches are less probable ones. The place where the top of the trunk meets the branches is the present. There are many futures, many branches of the tree, but only one past, one trunk.

35) As the future becomes the past, what happens to all those branches? The ever-advancing present acts like a chainsaw. When one of those many branches happens to be the way things turn out, when that branch transitions into the past, present-us cuts off all those other branches that didn’t materialize and obliterates them. When we look into the past and see only the thing that happened, it seems to have been inevitable. Why wouldn’t it seem inevitable from that vantage point? Even the smallest of twigs, the most improbable of futures – like the 2-3% chance – expands when it becomes part of the mighty trunk. That 2-3%, in hindsight, becomes 100%, and all the other branches, no matter how thick they were, disappear from view. That’s hindsight bias, an enemy of probabilistic thinking.

36) Hindsight bias – the human tendency to believe that whatever happened was bound to happen, and that everyone must have known it.

37) If we don’t try to hold all the potential futures in mind before one of them happens, it becomes almost impossible to realistically evaluate decisions or probabilities after. Once something occurs, we no longer think of it as probabilistic – or as ever having been probabilistic. This is how we get into the frame of mind where we say, “I should have known” or “I told you so”. This is where unproductive regret comes from.

38) By keeping an accurate representation of what could have happened (and not a version edited by hindsight), memorializing the scenario plans and decision trees we create through good planning process, we can be better calibrators going forward. We can also be happier by recognizing and getting comfortable with the uncertainty of the world. Instead of living at extremes, we can find contentment with doing our best under uncertain circumstances, and being committed to improving our experience.

39) One of the things poker teaches is that we have to take satisfaction in assessing the probabilities of different outcomes given the decisions under consideration and in executing the bet we think is best. With the constant stream of decisions and outcomes under uncertain conditions, you get used to losing a lot. To some degree, we’re all outcome junkies, but the more we wean ourselves from that addiction, the happier we’ll be. None of us is guaranteed a favourable outcome, and we’re all going to experience plenty of unfavourable ones. We can always, however, make a good bet. And even when we make a bad bet, we usually get a second chance because we can learn from the experience and make a better bet the next time.

40) Life, like poker, is one long game, and there are going to be a lot of losses, even after making the best possible bets. We are going to do better, and be happier, if we start by recognizing that we’ll never be sure of the future. That changes our task from trying to be right every time, an impossible job, to navigating our way through the uncertainty by calibrating our beliefs to move toward, little by little, a more accurate and objective representation of the world. With strategic foresight and perspective, that’s manageable work. If we keep learning and calibrating, we might even get good at it.

In Conclusion

References and Sources

1) Thinking in Bets – Book by Annie Duke

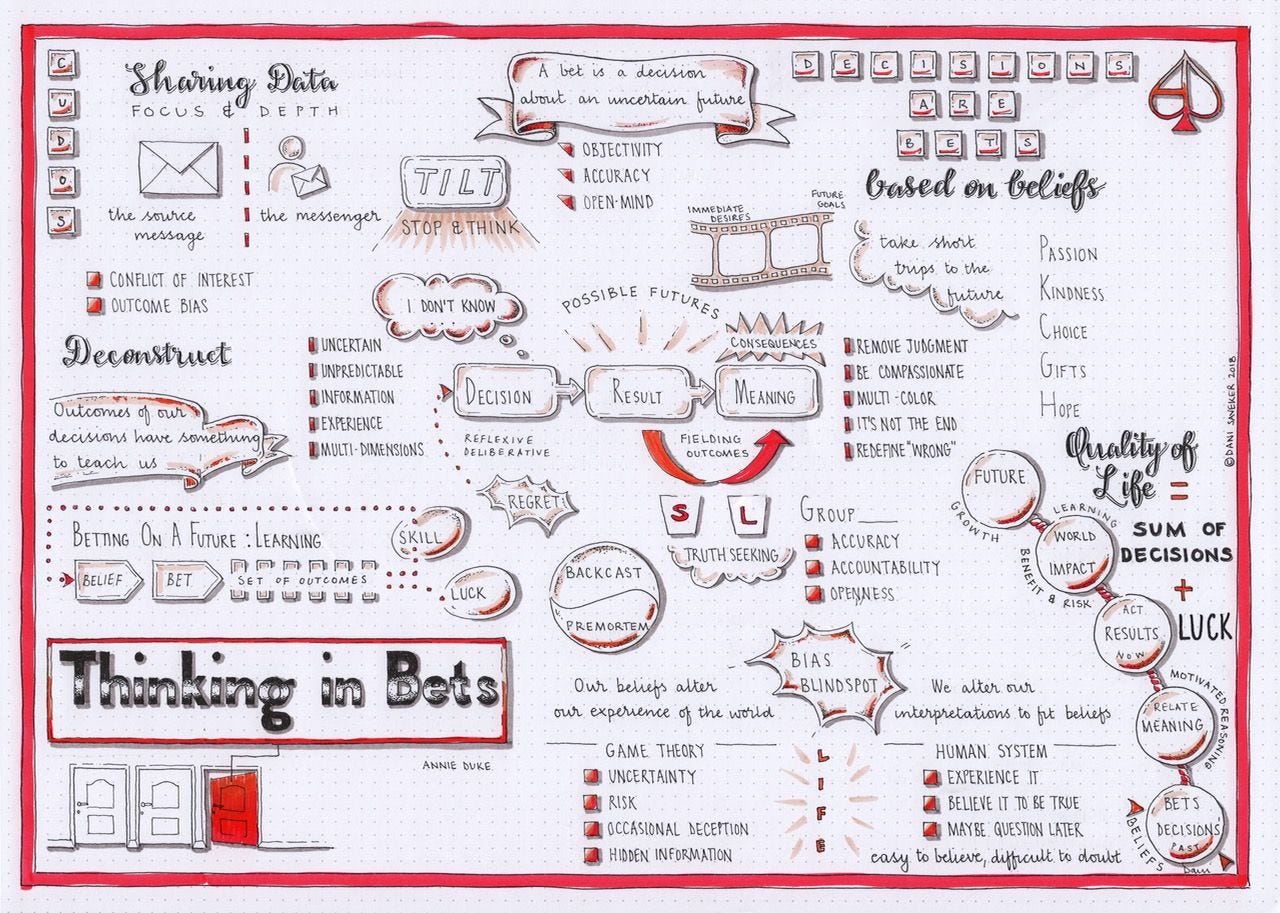

2) Thinking in Bets Mindmap: https://www.pinterest.ca/pin/412431278379127965/